- Home

- Jodie Chapman

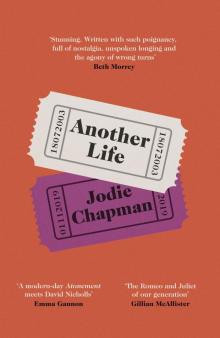

Another Life

Another Life Read online

Jodie Chapman

* * *

ANOTHER LIFE

Contents

Part One 2018

Anna

Late Eighties

2003

Early Nineties

2003

Late Eighties

July 2003

Early Nineties

Summer 2003

Summer 2003

Late Eighties

2003

Early Nineties

Summer 2003

Early Nineties

Summer 2003

Summer 2003

Summer 2003

September 1991

Part Two Summer 2003

Late Eighties

Late August 2003

2001

September 2003

1993

October 2003

November 2003

Part Three 2003

Summer 2013

2010

The Wedding, Continued

1991

2018

Autumn 2010

2003

Mid-Eighties

2012

Part Four 2018

Spring 1997

Late 2018

Three Days Later

The Next Day

A Few Days Later

Part Five A Few Weeks Later

A Few Weeks Earlier

June 2019

Three Weeks Later

Part Six Christmas 2003

2019

October 1990

Mid-Eighties

2020

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Jodie Chapman has spent twelve years working as a photographer and lives in Kent. In 2016, she was accepted on the Curtis Brown Creative novel writing course. Another Life is her first novel.

For Greg

and for

Roman, Remy and Val

Has it ever struck you that life is all memory, except for the one present moment that goes by you so quick you hardly catch it going?

– Tennessee Williams

Part One

* * *

2018

It didn’t work the first time.

My little brother jumped from the window of his Manhattan apartment building on Christmas Eve morning. His body fell seven storeys and landed in a skip filled with four feet of freshly fallen snow. It was the snow that saved him, cushioned the blow. It had drifted down all night and not yet had the chance to solidify. The soft snow was also the reason he wasn’t discovered until three hours later, when his cleaning lady walked into an empty apartment and found the window wide open. Seven storeys, four feet of snow and three hours of staring at the sky. Those are some damning odds.

I got the call as London rush hour was about to start. It had been a day of back-to-back meetings in stuffy, windowless rooms. There was little hope of catching a train home before eight, and I thought of the shit storm that would greet me when I walked through the door. But then there was a knock on the glass partition, and Jackie was waving. ‘Nick, there’s been an incident,’ she said as I stuck my head out, and I let the door swing shut as she passed me the phone.

When I walked into the hospital room twelve hours later and saw him hooked up to monitors, a mental image appeared of us as boys: doctor and patient, tying lengths of red wool from Mum’s knitting bag around our wrists and attaching them to cardboard boxes. We would recreate the sound effects – long, low beeps, the grave prognosis, a weeping wife. Almost thirty years later, we were playing again. Except the beeps were real and nobody was crying.

‘You look like shit.’

I nodded. ‘Where’s Tilly?’

He turned to stare out the window. ‘We broke up.’

He’d shattered the lower half of his spinal cord, they said. He was paralysed from the waist down and lucky to be alive. He’d never walk again. The doctor reeled them off like a shopping list.

I took each one like a bullet.

When he was finally ready to leave, I brought him back to his place and set up his new bed in the lounge. It had the best view in the apartment, which meant it didn’t face a brick wall and the poky windows into other lives. I remembered how he loved to look at the sky when we were young. We’d spend summers lying in the fields behind our house, hidden in long grass, racing planes the way you do raindrops on car windows.

Here, if I angled his bed a certain way, he could look through a gap between skyscrapers and see a patch of blue. So that’s what I did.

I stayed for nearly four months. Sometimes we watched TV or played cards, sometimes we sat in silence as if waiting for something to happen. I didn’t leave unless his cleaning lady was there to take my place. I’d thought of cancelling her in the first few days, but Gloria quickly became my lifeline, a chance for a breath of fresh air, and to look at something other than my rapidly fading brother.

I learned to weigh everything up. I locked the windows and opened one only when standing right by it. There was the issue of fire safety, but a mental-risk assessment decided there was a smaller chance of burning alive than a repeat of the incident. I threw out my razor and grew my first beard in almost a decade. Belts were banished, knives removed, all headaches endured. I was taking no chances.

I kept his phone away, on the side or in the kitchen. He asked for it rarely, but I kept it charged in case he changed his mind.

At least once a day, his phone would vibrate with a call from Tilly. He made no attempt to answer, and after a few weeks, I switched it to silent. She’d appear, looking at me over a coquettish bare shoulder, like a waifish ingénue – knowing Tilly, she chose the picture – and I’d watch it and hate it and think about smashing it. But I’d just let it ring off.

One evening, after a particularly bad day in which he hadn’t uttered a word, I snatched the shaking phone from the kitchen table and turned away from the door to the lounge to answer.

‘What?’

‘Mon amour. Oh, my sweet, poor Salvatore.’ The sound of her accent cut deep into the silence of the past month.

‘It’s his brother.’

‘Oh.’ She paused. ‘Is Salvatore there?’

‘He doesn’t want to speak to you, Mathilde.’ I knew how she hated her name.

‘Tell him I miss him.’

I thought about throwing her voice out the window. Let the snow cut her off. ‘Anything else?’

‘Tell him … tell him I am lost without him …’ I heard the crunch of her rosary beads against the mouthpiece and imagined her cocking the phone against her shoulder as she readjusted her hair in a mirror. ‘Tell him I broke it off with Chet as I could never love anyone like I love my Salvatore. Will you tell him that, darling?’

‘Mathilde?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Please don’t call again.’ I threw down the phone and swore under my breath, waiting for the sound of my name, but nothing came but silence.

As the cold began to ease, the city took on a certain softness. The trees that lined the concrete avenues began to bud, and people in the streets shrugged off their coats and layers. Everyone on the outside seemed to relax into the spring. Inside, Gloria and I remained on guard.

There was a shift in conversation a few days into April. It was my fault, my stupid desire for connection.

In the used section of a bookshop on the corner of 12th and Broadway, I found a small collection of poems by Longfellow. I couldn’t get back to the apartment fast enough.

‘Remember this one?’ I handed him the book and pointed to the title at the top of the page. The Children’s Hour. ‘How Dad would almost act it out? We could never sleep afterwards.’

Sal looked at the page and said nothing.

‘Why do you always want to remember things?’

I made beans on toast for dinner. I’d got pretty good at cooking over the winter, using the time inside to experiment with food and bring a sort of recklessness to the endless days. There was a posh version of ratatouille – I used pre-chopped vegetables, for obvious reasons – and I mastered the art of the soufflé. But that night, just like him, I made no effort. I couldn’t form my anger into words so I served it to him instead, and I set the tray down on his over-bed trolley table with a bang.

He looked up at me in surprise, and I felt a burn of self-loathing.

I woke in the night and heard him cry. I stumbled into the lounge and there he was, propped up on his elbows, staring at his dead legs and sobbing like a baby. His skin was cold and clammy in my arms, his T-shirt soaked through.

‘I can’t,’ he said, his voice breaking like a kid’s. ‘I can’t see her any more. She’s there in my head, when I close my eyes. But she never speaks to me, and I just wish she would speak so I can hear her voice again. Where is she?’

I knew he wasn’t talking about Tilly.

‘I don’t know, Sal.’

‘Will we ever see her again?’

I shrugged. ‘Perhaps. Or not. I don’t know.’

Sal always wanted answers. In our early teens, our Aunt Stella got us work experience in her office. It was a company selling insurance and our first job was inputting new clients on to the computer system.

The woman training us, Mandy, had a voice best described as a dirge. She had a mass of permed hair and glasses like bottle-tops, and when she made coffee using water from the tank on the wall, scale would form frothy pools of bubbles on the surface. Sal made a vomiting sound when she made one on our first day. ‘You should get that cleaned,’ he said, pulling a face. ‘Oh no, I love it,’ she replied, smacking her lips. ‘It’s like a cappuccino.’

Mandy would sit and direct us between slurps as we entered information on the screen. Looking back, she can’t have been more than forty, but she seemed ancient to us. She’d held her job for decades and was clearly very satisfied with it. Her hamster cheeks wobbled with delight at the modicum of power she held over us. ‘Enter the name, select the prefix from the dropdown, then click “next”. Enter the address, put the postcode in the box marked “postcode”, tick the little box, then click “next”. Then—’

‘But why?’ said Sal.

‘Why what?’

‘The little box. Why do we tick that?’

Mandy frowned. We could sense the cogs turning. ‘You just do.’

‘Does it set something off in the background?’ he said, tapping his fingers. ‘What’s the purpose of the tick? The box? I mean, why are we ticking it? And what happens if we don’t?’

She squirmed in her chair, uncomfortable at being taken off-script. ‘I-I don’t think it really matters why. I just know that’s what you do. It’s never been left unticked.’

Sal was deliberately avoiding my look. He gave a long, bored sigh and spun his chair back round to face the screen. ‘Fine, whatever. I just think we should know the reason.’

That was the only time Sal ever worked in an office. But the asking of the why never ceased.

‘Tell me about her,’ he said now, gripping the sheet. ‘I’m starting to forget the details and I can’t. Tell me what you remember.’

I drew back. ‘I don’t know what you want me to say.’

‘The truth. I want the truth. Please.’

I swallowed. ‘I tried to talk about Dad earlier—’

‘He’s not the one I want. He’s not the one you want either. Why can you never talk about the things that matter?’

I looked out at yellow headlights cavorting in wild lines across the road. Neon flickered in the gloom. On the other side of locked windows, the world continued on.

Sal rubbed his eyes with the backs of his hands. ‘I need to see her again. I’m done waiting.’ He gestured at the shape of his legs under the sheet. ‘What is there left for me now?’

‘You know she loved you,’ I said after a while. I sat on his bed and faced the dark city, alight with a thousand bulbs. ‘And you know it wasn’t your fault. These things just happen.’

Sal looked at me like I was a fool.

‘Do you still not get it after all these years?’ he said. ‘It was all my fault. I’m the reason why.’

If I had known that would be the last time, I’d have pulled him close and hugged his cracked legs and warm heart. I’d convince him that there was much more to come, spout some shit about the future being brighter, and drill locks on every cupboard door.

But what happened is this.

I fell asleep curled up at the end of his bed, and when in the morning Gloria arrived as usual, I took a shower and decided to walk the fifteen blocks to the bakery on Spring Street to get the little cakes Sal loved. As I passed through the lounge, I could see him asleep on the bed, his hair pale in the morning sun.

Outside, New York was picking up heat. I crossed the road to walk in the shade and passed two girls of about nineteen, one laughing at something the other had said. They wore summer dresses and their shoulders were bare, and as I turned my head to look at them, I thought how life was a mixture of sad and beautiful and there was nothing you could do about it.

My phone rang as I walked back from the bakery. It was a little after 8 a.m.

A courier had buzzed the apartment with a delivery and refused to climb all seven floors for a signature. Knowing it was some urgent papers I’d been awaiting from work, Gloria had done a quick check of the windows and slipped out. She was gone no longer than six minutes, she said.

In that six minutes, my little brother threw himself off his bed, pulled his broken body along the carpeted floor to the galley kitchen, where he opened the door to the sink cupboard and unscrewed the cap and swallowed what remained of a bottle of bleach.

I’ve thought of that final day often. Of my foolish excitement at the book of poems and a shared memory, of his face when I gave him his tray, and then I always remember that, for his last supper, I made bloody beans on toast.

I know people love New York.

I know it’s a place that exists within everyone, in Christmas movies from childhood, in Bob Dylan and all those dead Beat poets, in Sal who came on a holiday visa and never left, and in others who talk of returning. Even people who’ve never been feel like they know it. I admit that I used to think about going, of taking off for City Hall, of holding hands in the streets, of loving it because she did. When I imagined myself there, it was always with her and as if I had won somehow.

But my first visit there was a rescue mission, and when I left, it was with my brother in a box. I had failed, and it felt like the city had failed me too.

I know people love New York.

I hate it.

Anna

2003

I met her at the beginning of summer. She wore dresses with thin straps that cut into her shoulders, and I’d watch her body when she wasn’t looking. It was a game I’d play in my head. I’d repeat the mantra, don’t look at her chest, don’t look at her chest, so I’d look at her lips instead. That seemed less creepy, somehow. But her body … the way her dress skimmed her body.

I know I should say it was the blossom. That I recall the season because of scattered blossom left over from spring. But whom do I kid. It’s the dress and her body in the dress.

Fuck Keats. Every man is the same. We don’t remember blossom.

Late Eighties

They say you begin to forget.

An event occurs and your brain records the details, then over the years, the picture fades until you only retain an outline. With Mum, it was the opposite. At first, when she disappeared, she went from my mind too. I guess I blocked the memories out for obvious reasons – self-preservation, perhaps – but as I grew up, there were times when they’d come flooding back. It was as

if they had been locked away for safekeeping, until I was old enough to handle the pain.

Some were linked directly to my senses. I’d hear a song or walk down a certain street, and a switch would flick as it came back to me. I’d go very still and tease the memory out, and hope imagination would take care of the rest.

Mainly it’s a feeling or a sound.

Let me explain.

I remember the skin on her fingers, how it was rough to the touch like a bandage. Her hands were dry from the water and soap of the endless washing-up we gave her, and there were little tufts of bitten flesh around her nails. Sometimes she would cup my face with her hands, and the sound of her skin on mine was like scratching.

Sal told me once that his strongest memory was playing with her hair.

She would sit in the pale green armchair that was covered with birds and flowers – the one she and Dad had bought from Harrods with their wedding money – and then she’d let down her golden hair. Sal and I pretended to be hairdressers, taking turns to brush and fill her curls with slides. ‘Fix me up, boys,’ she’d say as she settled into the chair. ‘Make me look pretty tonight.’ Her hair was thick and warm, and with every stroke of the brush, strands would fall to the ground. I wish I’d cut a lock and put it in an envelope, the way some parents do when they first cut a child’s hair. For the future act of remembering.

And sound.

One time, she sat on a bench and watched as we played on a climbing frame in the town centre. The concrete slabs shone from the morning rain. I was doing the monkey bars, and they must have been wet because I slipped and fell and twisted my ankle. As I lay clutching my foot, she came running towards me. It’s hard to describe, that particular sound of her leather shoes on the damp ground, but it was like a wet, polished knock. About five years later, I was walking out of school and a girl ran past me. She must have been wearing the same kind of shoes and it must have been raining, because her feet made the exact same sound as she ran.

Another Life

Another Life